A miserable March day, overcast and cold, rain spit on our faces. Parents, spouses, and children all locked in the same nightmare, a bad dream, an insanity sending men and women off to war but somehow we agreed to let this thing happen. Behind our kids, behind our soldiers standing at attention, there is a graveyard. I am not amused by the irony; I am a part of it. This was the first day of what would be a God-awful fifteen months. On Mother’s Day, two months later, our son the soldier and his National Guard unit deployed to Iraq.

* * *

Taken from his mother by the doctor, passed to a nurse who held the newborn aloft to ascertain its gender, Erik grimaced and kicked.

“It’s a boy,” the nurse declared.

Our son, a gift-wrapped in placenta, was cleansed and given to me.

Our son, a gift-wrapped in placenta, was cleansed and given to me. His body was muscular and vital. His hair was the color and consistency of corn silk, a fine blond that billowed in response to my breath. His eyes were dark blue, mottled with flecks of gray. As the strain of terror eased from his face and the fluttering of the nearly translucent lids slowed, I believed at that moment that the tiny, defenseless child I held sensed my paternal presence and was comforted. I slipped the child into the arms of his mother. Tears of joy breached Pam’s eyelids and fell down her flushed face; I wiped the sweat from her brow.

Of our three children, Erik seemed the least likely to grow up and become a soldier. Josh the tougher, wiser, pragmatic big brother, maybe; Rachel who walked at the end of her seventh month and uttered full sentences at eleven months and had the temperament of a hockey player, maybe – but not Erik.

Breaking out in tears when my bedtime stories turned tragic, it was evident early on that Erik was a gentle soul. Even his body moved in coordination with a temperament that wished to come and go with out doing any harm. Lithe and wiry, he went about his business quietly, padding softly from one thing to the next, and although armed with an impressive vocabulary and sharp intelligence, he was never loud. He was quick to smile and even quicker to respond to anyone or anything in need of rescue. When he ran, his fine, blond hair would lift and fall in rhythm with his stride. I remember it shone like the finest silk in the sun. He was a joy to raise.

* * *

Our son became a soldier when he lost his academic scholarship. Pam and I suggested that he move home, find a job, and save some money. If he did, we would help with tuition but Erik had other plans – he’d join the National Guard.

The idea terrified Pam, but I thought it great that he had come up with his own solution, and it never occurred to me (it was just five months after 9-11) that America would invade and occupy Iraq. Heck, it was the National Guard – show up every fourth weekend, and maybe, if the Pistons won the Championship again, deploy to Detroit and put out fires.

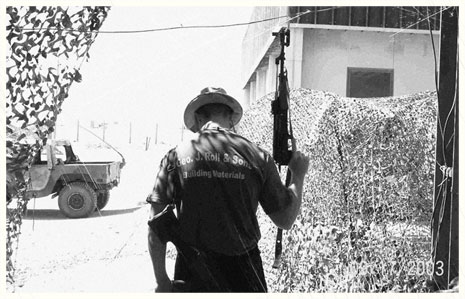

So in January of ‘02, joining the Michigan National Guard, Erik became our son the soldier.

Pam and I were sickened by “Shock and Awe” – not just because we worried about our son’s future, but because it shamed us and bloodied our hands. This was not protecting America from terrorists; this was implementing a new foreign policy. It had nothing to do with either national security or international diplomacy. It was naked aggression, the actions of an empire closing in on itself.

These are just words, arranged to convey my feelings – my rhetoric versus their rhetoric – but it isn’t words that pierce flesh and shatter bones. It isn’t words that fall from the skies and obliterate children and villagers. It’s our sons and daughters that carry out war.

Pages: 1 2

No Comments so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.